1st November 2023 By Contributor | contact@foodticker.co.nz | @foodtickernz

Tapping into the average person’s concerns over the environment may help spur collective action and beer could be a good test, says the World Economic Forum’s John Letzing.

The Industrial Revolution was good for beer. New tools put a more reliable product into more mugs.

The global warming wrought by the Industrial Revolution? Not so good.

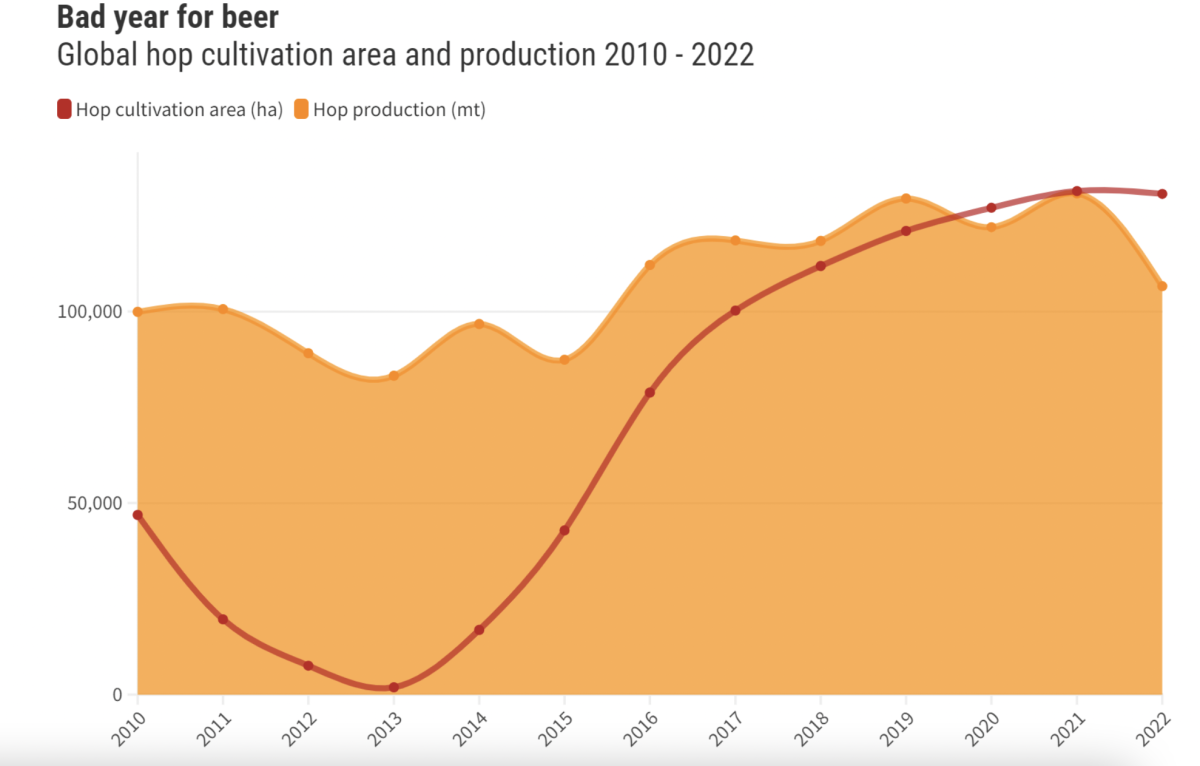

A recent study found that yield and quality in hops-growing regions in Europe fell sharply after 1995, and that warmer, drier conditions will probably further deplete this key beer ingredient by 2050. That means the changing climate could make a lot of what we drink taste worse, and cost more.

Scientific evidence of beer’s impending decline has been mounting for years. But so have scientific attempts to save it. In light of the devastating nature of other climate impacts being felt around the world, these efforts might seem pretty superfluous.

Yet, beer is a great way to hit people where they live. It’s among the world’s most popular beverages. Czechs drink 161 litres per person every year. Americans prefer it to wine, not least at tailgate parties. The Chinese are consuming more now, and at last year’s World Cup soccer fans from Ecuador briefly cheered for it instead of their team. Duffman, the tireless beer mascot in “The Simpsons,” is multilingual.

There’s a school of thought that tapping into the average person’s sense of ecological insecurity may help spur more collective action. If we’re looking for a good way to test that, we could do worse than beer.

Help is in the offing, experts say – in the form of better irrigation techniques, and new hops bred to be drought-resistant. “There are a lot of scientists working on this,” said Scott Lafontaine, an assistant professor in food chemistry at the University of Arkansas in the US. “Whether or not we can keep up with the pace of climate change, that’s the question.”

The recently published study of European hops cultivation focused on a part of the world where the adoption of new ways of doing things has lagged among some centuries-old breweries.

More than half of the world’s farmland used to grow hops is in Europe. The bulk is in Germany, home of the Oktoberfest, but the Czech Republic and Slovenia are also big producers. All together, the region usually churns out more than 5,000 metric tons of alpha acid, the secret sauce in a hop that gives beer its distinctly bitter taste, every year. A lot of that gets exported to foreign markets. Last year, there was less to go around.

Alpha production declined by 40% in Germany compared with 2021, and by 56% in the Czech Republic, according to BarthHaas, a German hops distributor. “The effects of climate change are becoming apparent,” the company said.

The predominant hop-growing area in the US, the world’s other major supplier, also suffered from extreme conditions last year. One of its coldest and wettest springs on record was followed by scorching heat that “ripped across” the region and depressed yields, Hop Growers of America reported.

Irrigation and hop breeding to the rescue?

There’s likely a lot more of this type of weather yet to come.

The first way to adapt is through better water use, according to Javier J. Cancela, an agronomic engineer at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

“The hop is a very singular crop,” Cancela said. Hop vines can shoot up from the soil to six meters tall in less than a month, which requires a lot of water and nutrients. Europe has generally lagged the US on the introduction of irrigation, according to Cancela.

Still, Cancela noted that European farmers grappling with increasingly sparse and erratic rainfall have started deploying more efficient drip irrigation systems, like those developed in Israel, a semi-arid country. “They can get [agricultural] production with the minimum amount of water possible,” he said.

Smarter water use may not be enough to make up for shortages in the future, though. “Projections aren’t necessarily rosy in that realm,” Lafontaine said. But new types of hops are being engineered that can be more resilient to drier conditions – think more Ivan Drago than Frankenstein’s monster. “Tango,” a cross between US and German breeding lines, is one promising version.

Tango’s aroma variety is “a good all-rounder,” according to BarthHaas; 32 hectares were planted with it last year. Still, the companies making the final product need to take interest. “There might be some hesitation on the part of some of these mainstay breweries that have been around a long time,” Lafontaine said.

Hops were a relatively late addition to the science of beermaking, and were initially a tough sell. More recently, demand has spiked. The aromatics this ingredient produces have helped fuel a beer revolution in the US, where the total number of breweries increased by 960% between 1995 and 2020.

Innovation could solve some climate-related challenges. Technology such as low-cost sensors for more precise monitoring of hop fields will be “critical,” Cancela said. Indoor, hydroponic systems for growing hops with far less water are being explored. So is genetically modified yeast that might even eliminate the need for hops.

But more fundamental change – in terms of what’s grown and where, and the beverage that results – may be inevitable. “We as humans are going to adapt, and modify,” Lafontaine said.

That idea might not be so welcome in more tradition-bound corners of the beer world. Places where words like “Bierernst” (“beer serious”) are part of the lexicon, or a hop-growing area can qualify as a World Heritage Site.

But a warming planet is already revising the global agricultural map. Cancela noted that it wasn’t so long ago that the notion of growing good wine in the UK seemed absurd. No longer. The country’s area under vine has grown by 74% in the past five years, to roughly 4,000 hectares – which is expected to nearly double in the coming decade.

The cultivation of high-quality hops could follow a similar trajectory. “Maybe we’ll see it in Norway, or Finland,” Cancela said. “Hops in Siberia? It’s impossible to predict.”

John Letzing is digital editor of strategic intelligence for the World Economic Forum.

Republished from the World Economic Forum in accordance with Creative Commons Attribution. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

© 2024 Business Media Network Ltd

Website by Webstudio