22nd January 2024 By Contributor | contact@foodticker.co.nz | @foodtickernz

New technologies can play an important role in creating more robust, sustainable and affordable food production ecosystems, according to Fork and Good chief executive and co-founder Niyati Gupta.

“Remember hamburger chains, always real beef, remember hot-dog stands?” Twenty years ago, Margaret Atwood imagined a dystopian future where meat products became a luxury again. Two decades from now you may be saving up your pay cheque and making reservations to eat a rare burger the price of gold or choose to relegate it to nostalgia.

At COP28, food was a key tenet of the COP28 agenda for the first time because livestock accounts for about 15% of global greenhouse emissions, the second largest contributor after energy for our homes. If current trends for food demand and production continue, emissions from the food system alone would likely push global warming beyond 1.5°C.

Most of us have become aware of animal agriculture’s contribution to climate change, but not vice versa. In fact, one of the first places most of us will feel climate change will be on our plates. Fortunately, novel technologies are being developed to counteract the impact of climate on agriculture and the impact of agriculture on climate.

How climate change impacts meat supply chains

Climate change impacts meat supply chains in three major ways, making them less productive and more expensive. These are:

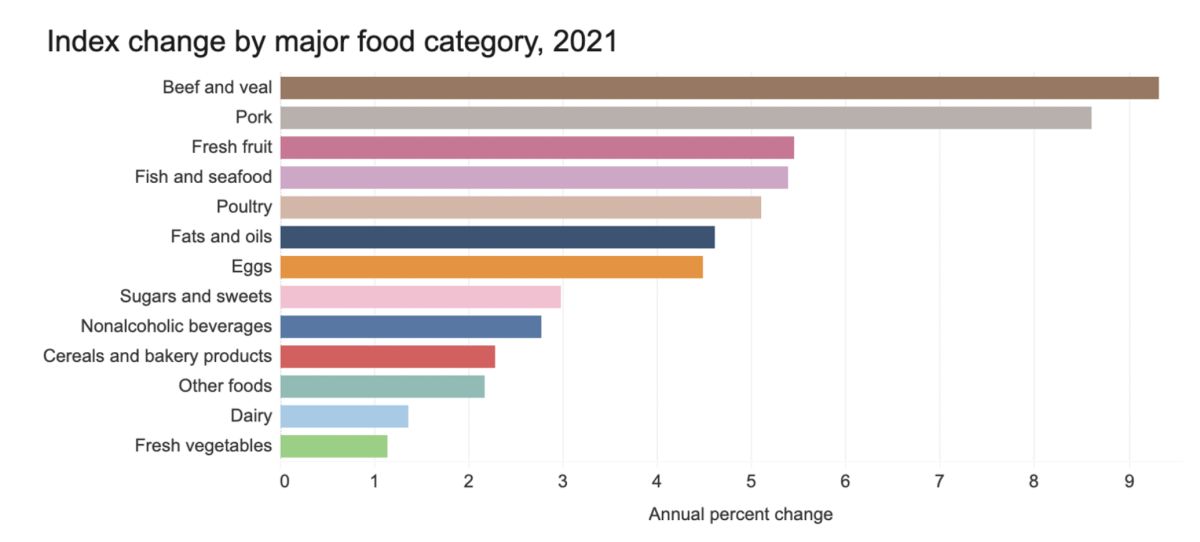

The impact of changing ecosystems on meat supply chains is undeniable, and the net result is more volatility and higher prices, as highlighted by the rate of inflation for beef and pork prices in the US.

Despite this, global demand is not letting up – we love our meat. Only about six countries in the world have reached what can tentatively be described as “peak meat”. Meat consumption per capita is still rising in the US, and growing even faster in other parts of the world where incomes are rising – like China, Vietnam and Brazil.

China is now the world’s biggest meat consumer at 53 million tons of pork and 10 million tons of beef and is still at only 50% of US consumption per capita.

Behaviour changes linked to improved incomes and more meat-heavy diets are far more significant than population increases in terms of how much meat we eat – one-third of the world still doesn’t consume enough protein for their nutritional needs.

What this means for consumers and food security

Ultimately these climate impacts on meat supply chains will lead to meat shortages, price increases and limit access to highly bioavailable animal protein to the lucky few. We’re already seeing this in some parts of the world.

The UK recorded the lowest meat consumption on record last year, a 26% decrease in beef, pork and lamb since 2012. Why? A combination of the rising cost of living and that meat is too expensive. This has had a far greater net impact on meat consumption than the rise of vegan, vegetarian and flexitarian diets.

Protein diversification is part of the solution, but behaviour change is hard and patterns of how we eat are deeply culturally ingrained. Despite a vegan diet gaining in popularity, vegans only account for about ~1% of global demand, so relying on consumer dietary change is not enough.

Meat is tasty and most of the world would like not to be priced out of animal protein. This means we will persist in our quest to obtain more cheap meat and continue the vicious cycle by having increasingly intensive animal agriculture systems facing enormous risk.

So how do we ensure our grandchildren can still try burgers, eat dim sum, or enjoy a chicken curry? New technologies can play a role in more robust food production ecosystems and help meet our 1.5ºC climate change target.

How technology can keep meat on our plates

One way is to build climate adaptability and risk mitigation in our current systems. For example, heat-resistant feedstock crops or integrated mixed-use farming systems that are more resilient to changes in climate. For example, Pairwise is trialling a CRISPR-edited corn with more robust yields to sustain productivity.

Advancement in technologies like cultivated meat, cellular agriculture and new proteins offer an additional pressure release valve.

Cultivated meat grows animal muscle and fat cells with a lower feed and water intensity, while having the same taste and nutritional value as meat. Fork & Good’s cultivated pork, for example, uses 10x less water and 4x fewer calories than conventional hog rearing without relying on an animal so is more heat and disease resilient.

Cellular agriculture also has similar advantages. Precision fermentation for dairy and eggs from companies such as The Every Company enables us to get the same proteins without the need for animals.

Of course, the role of these technologies will be dependent on scalable solutions that improve affordability in the long term.

For example, at Fork & Good research efforts have brought down costs 300 times over four years. We must also consider where protein access is low and nutrient deficiency high, to tailor the forms of animal, plant or cellular agriculture introduced to increase access to protein.

Given the scale of the problem, it will be important to consider a multi-pronged approach and support innovation in the sector by promoting investment in new technologies such as cultivated meat.

Scientists, policy-makers and the food industry have an opportunity to work together to speed up the use of sustainable practices and support the scale-up of new technologies.

Ultimately this will allow future generations to experience the variety of foods we enjoy today, and even keep the occasional burger on the menu.

© 2024 Business Media Network Ltd

Website by Webstudio